Solitude

SeedKeepers deserves my heartfelt thanks for selecting me as the writer-in-residence at Apple Blossom Farms on Beaver Island, MI, this year. I experienced two weeks of solitary reflection and writing amidst abundant opportunities for natural and historical inspiration. One lesson I learned is that some of my most exciting writing derives from tensions at the boundary between human nature and wild nature.

Apple Blossom Farm is located in the approximate center of Beaver Island and comprises 40 acres of an original 300 acre parcel settled by a mormon, Daniel Gallagher, around 1840. The cedar timber form of his original barn remains and makes a strong and surreal impression resting alone in a lush meadow. The road leading to the farm is named King’s Highway, referring to James Strang, a break-away mormon sect leader who proclaimed himself Divine King of Heaven and Earth but was assassinated following years of tension with outsiders and victims of his sect’s crimes. I highly recommend The King of Confidence by Miles Harvey for a thorough and entertaining telling of that history.

More recently, the property was used for grazing cattle, but had been abandoned for more than 20 years prior to its purchase and slow rehabilitation into Apple Blossom Farm. The property today is not a working farm, but its owners intend to explore regenerative practices that restore native habitat. For now, the fields grow deep in lush grasses, bracken fern, and numerous wildflowers. The forests are relatively young succession growth from former pastureland and comprise mostly birch and arbor vitae. Old and wild-seeded apple trees were loaded with fruit during my stay.

The primary experience there is of stillness. I had the good fortune to arrive on Labor Day, which marks the end of the summer season even more dramatically on Beaver Island than elsewhere in northern Michigan. A farm caretaker was there for several days but left me alone on the property for more than a week. The only sounds throughout the days were from crickets. Only occasionally did a work truck pass or small commuter plane take off from the airstrip up the road. This suited the character of the farm, which has qualities of a place abandoned in time. The current owners described finding the wallet and personal effects of the previous owner still lying out when they took possession of it twenty years after his passing.

With every step I found my attention drawn down to small and quiet things, such as Lesser Fringed Gentian, pictured below, which were thrilling to see for the first time in a landscape I thought had few surprises left to show me.

There are no longer bear, wolf, or big cats on the island. The largest predator species there is coyote, which could be heard playing and hunting every night after dark. Their at times haunting and at times preposterous vocalizations, along with snorting and stomping white tailed deer and crying opossum, were some of the only sounds to break the nighttime quiet.

One morning I woke before dawn after a long night of storms and decided to get started early. I stepped outside the tent around 4 a.m. There was heat lightening far to the north that illuminated the surrounding field and old Mormon barn. I didn’t want to use a flashlight so let my eyes adjust to the moonless dark. When I stepped onto the path I thought I saw a fallen piece of reflective cloth from a shoe or jacket. As I knelt down the light throbbed and dimmed. Then I realized there were dozens and hundreds more of these lights glowing all around. The lightening bugs had been driven deep in the thick pasture by the hard rain. This offered me a vision of life from their perspective, their society, along with countless other beings living deep in the architecture of the field. Among them were the snakes and frogs, praying mantises and caterpillars, I saw each day. A feeling of beautiful alienation overcame me. It was a moment to set aside what I thought I knew and what I thought possible. I placed each footfall carefully after that and took a long time crossing the field to make my morning coffee in the farmhouse. Each few steps I paused to take in the beauty of the phenomenon, unsure if I would ever see anything like it again.

I hadn’t been there long before realizing much of my time was spent thinking about human nature more than wild nature. In the background of the trip were numerous career and creative duties, family obligations, transitions of life phases for aging loved ones, and the natural tension that accompanies any effort to step away from modern life. There was also my boyish fear of being alone in a tent in the dark, my adult ego’s fear of failing at any number of things I had set out to do, and my resentful mind seeking to cast doubt onto everything as a means of self defense. It never ceases to amaze me how nature and solitude hold up a mirror to things I otherwise cannot see or often do not want to confront. The only noises I could truly complain about were those between my two ears or locked in my heart.

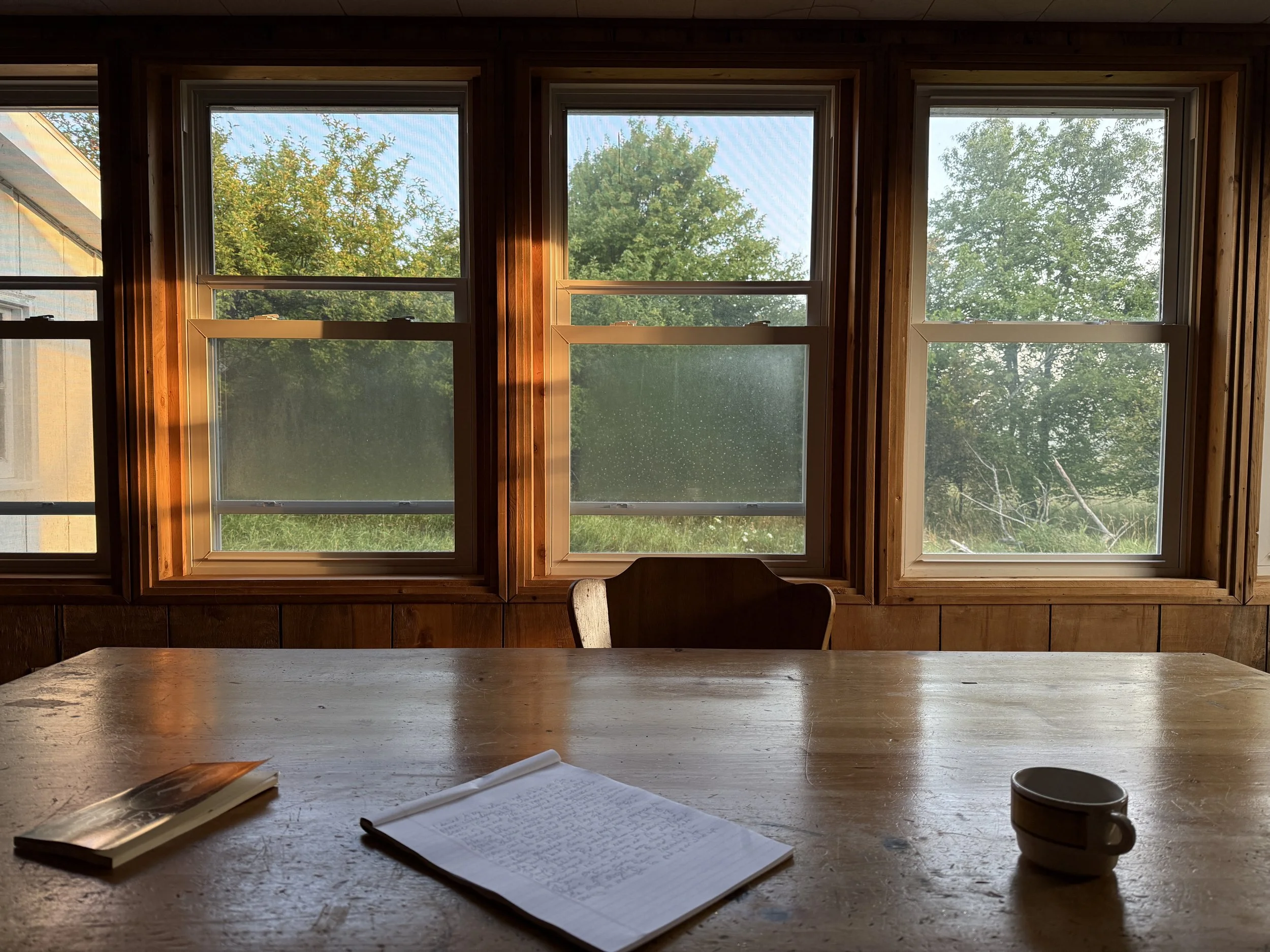

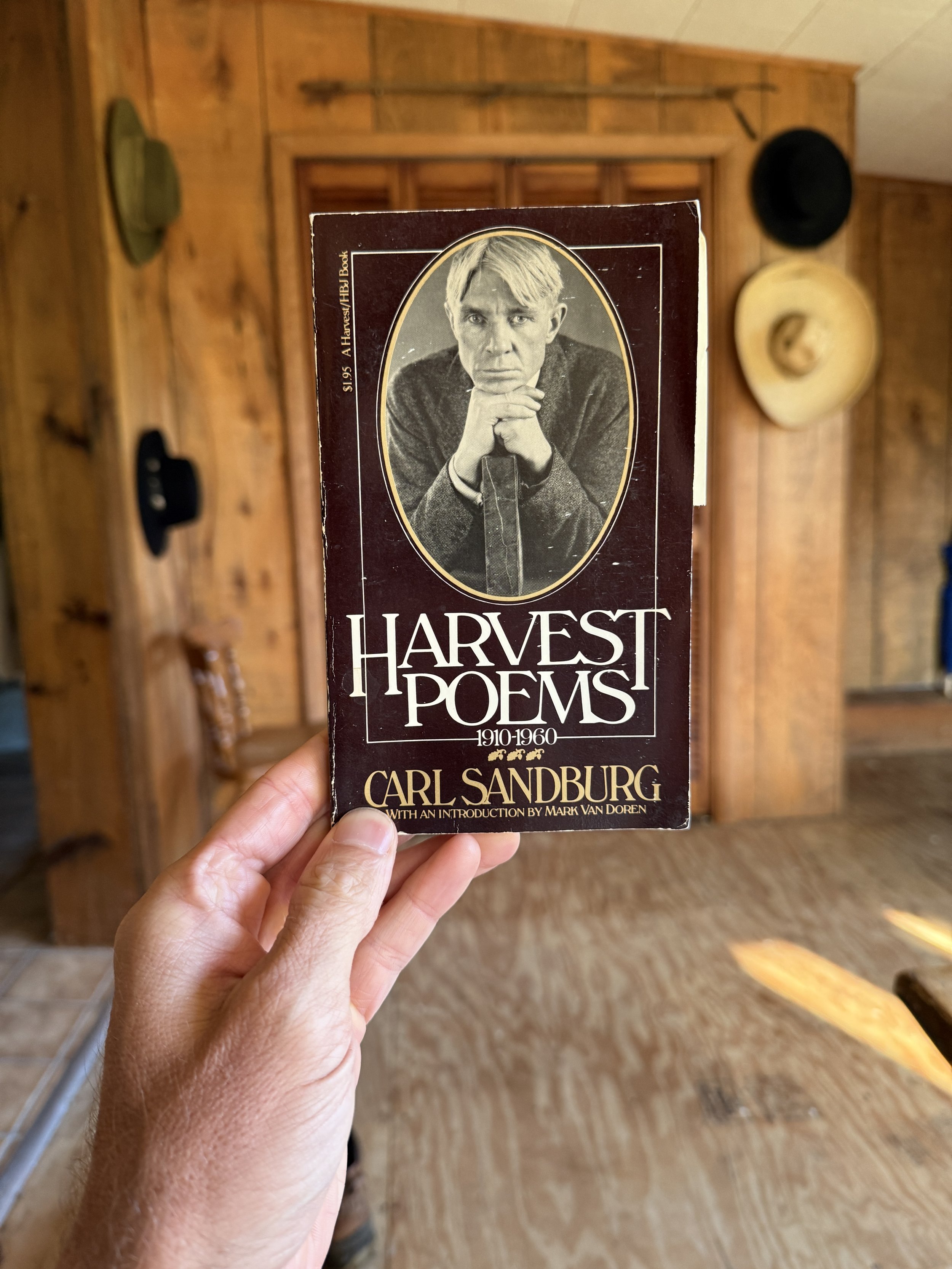

I had come to the farm to write new poems about the boundary between human nature and wild nature. Unexpectedly, I found myself working out many of these tensions as prose in journal notebooks. But I have learned over the years not to hinder the creative impulse. It must be followed and respected. I don’t necessarily get to decide what I write only if I write.

As it turned out, this benefited my poetry writing practice significantly by keeping me in an open state to move emotionally and mentally where I needed to without question. The poetry that I proposed to write during the residency, and that I did in fact write, developed freely as inspiration throughout each moment of the day, whether I was meditating inside the Mormon barn, walking in the nearby marshland, swimming at a sweeping deserted beach, or waiting for the washing machine to finish at the laundromat. It is crucial as an artist to stay loose, limber, and willing, and to surprise myself at every turn to keep the process and work fresh. I began significantly more pieces than I expected I would. The solitude on the farm eliminated any sense of pressure to produce something, which paradoxically freed me to be far more productive than I had any right to expect. I was rewarded with a degree of patience and focus that I am not accustomed to demonstrating at the writing desk.

In addition to the notebooks, and new series of poems, I detailed a list of longer projects that I have been putting off but need, in the deepest sense, to write. It is a familiar feeling, this need. I will, for example, be thinking about a piece of writing when I am seized by a unique combination of total peacefulness with eagerness to act. The total peacefulness comes from absolute intuitive clarity of what I need to do in order to fulfill my potential and be of service through my art. The eagerness to act comes from acute awareness that this gift is precious within my fleeting life.

The Beaver Island Public Library also deserves gratitude for hosting my reading and presentation. The audience was very engaged and stayed for a long conversation afterward. It was a pleasure to share aloud with an audience for the first time poems that I will include in a coming collection on the themes of nature, gardens, and agriculture. To me, at least, these topics are inherently linked to themes of spirituality, human nature, and aesthetic experiences. I was happy that listeners responded to those connections in the writing, which also showed through in the few rough drafts I read of poems begun during the residency. The time on the island was transformative to my work and leaves me with that feeling I tried to describe of peacefulness mixed with eagerness to act. I look forward to bringing new works to readers and listeners over the coming months and years.